Confidential communication is not only important, but necessary in plenty of scenarios, from online purchases to communicating military intelligence. In order to achieve trust and confidentiality in communications computer scientists invented cryptographic protocols. While the theory behind cryptographic protocols has been rigorously formalized, their implementations are not and prone to bugs. This space is fertile grounds for formal verification of computer programs, which has had success in both academia and industry[1][2].

In this blog post we will formalize a component of many cryptographic protocols, permutation networks. According to World War II historian David Kahn[8], the most common message German intelligence officers would transmit is “Nothing to report”. Even though the passwords to the infamous Enigma machine would change every day, if an American spy intercepted the encrypted message “Abguvat gb ercbeg” he could quickly compare the lengths to the very common “Nothing to report” and infer that “N” encrypts to the letter “A”, “o” to “b” etc, soon allowing a spy to decrypt the entire alphabet. Now if the letters in the encrypted message where rearranged (or permuted) in a seemingly random but reversible way, that would prevent this kind of attack known as “known Ciphertext attack”, entirely.

Permutation networks do exactly that. Using a network of configurable switches, they rearrange the input, such that their output is always a permutation of the input. They are an important part of the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)[5] that powers all of web communication technologies.

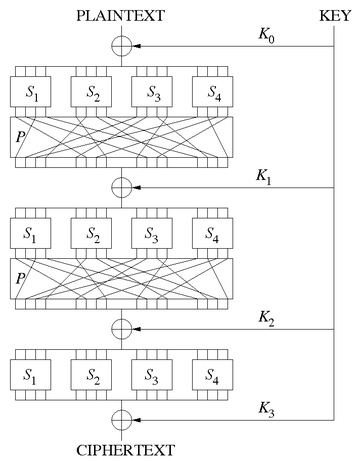

Fig0: An algorithm in the AES family with substitutions (S) and permutations (P)

We will not discuss substitutions here, if only in-passing and as a nod for future work. We will now see some key properties of permutation networks and then proceed in the design and implementation of our formalization.

Useful properties of permutation networks

Here are some compelling properties of permutation networks.

- They are configurable; a network of

nswitches requiresnconfiguration bits, which allows the network to perform2^ndifferent permutations. - They are reversible; for all outputs, if we run the network backwards we will get the original input.

- They are scalable; for inputs of size

na poly-logarithmic number of switches are required. There are many constructions following Benes’[1] original work that improved on that boundary, for example Waksman networks[2], although for all the switch bound isO(nlogn). - They are parametrically polymorphic; this is a property that is not often discussed in the same breath as permutation networks, but we found to be true. Our construction is parametrized by the type of elements as well as the size

of inputs. Given the right configuration bitvector, a permutation network is finite map

f: forall a n, Vector.t a n -> Vector.t a n.

Design

In order to define permutation networks, we first define general configurable circuits and their compositions.

Circuit framework

We define a general circuit framework in Coq, using dependent records parametrized on the type of inputs, number of inputs and number of outputs.

Record circuit {a: Type}(inp out: nat) :=

circ {

ns: nat;

f : Vector.t bool ns -> Vector.t a inp -> Vector.t a out;

}.

The ns attribute stands for number of switches, the configurable binary components that determines how inputs are rearranged. The finite

map f represents the denotational semantics of the circuit, given ns configuration bits, it then maps inputs to outputs. With this

design we can perform circuit composition easily; by adding the numbers of switches, inputs and outputs accordingly while using

function composition for the extensional behavior of the composed circuit.

Finally, notice how all our circuit constructions are parametric on the type of inputs = type of outputs. This does restrict our constructions and perhaps a more general definition parametrized on both input and output types would be more reusable.

A binary switch

The fundamental block of our networks is the binary switch. It is a configurable switch with two inputs that map to each other by identity when the switch is configured with a ‘0’ bit or swap places when configured with a ‘1’ bit.

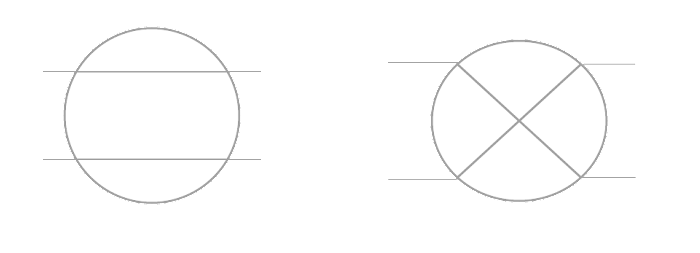

*Fig1: A 1-bit binary switch, left is the switch at the 0 position (identity) and right is the switch at the 1 position (swap). *

Here is the Coq definition that corresponds to the binary switch using the circuit framework above.

Definition switch {a:Type} :=

@circ a 2 2 1 (fun c => if hd c then id else (fun v => tl v ++ [hd v])).

Circuit composition

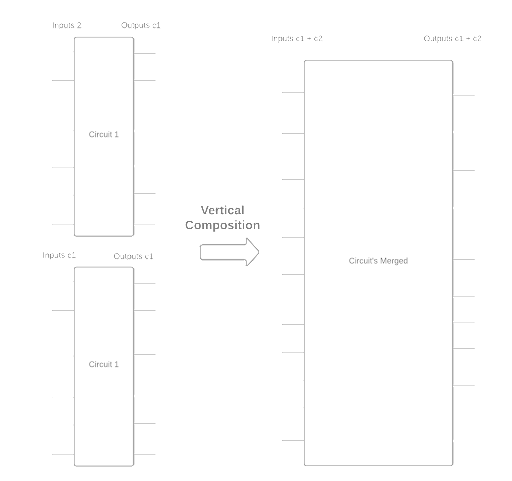

Vertical

The first composition we define is vertical composition.

Fig2: Vertical circuit composition

It takes a circuit c_1 with inputs i_1 and outputs o_1

and a circuit c_2 with inputs i_2 and outputs o_2, composing them vertically then gives a circuit with inputs

i_1 + i_2 and outputs o_1 + o_2. Here’s how we define vertical composition in Coq. Notice the use of splitat to

take the first ns c1 configuration bits and pass them to the first circuit, leaving the rest for the second circuit.

Definition vertical_compose {a:Type}{i1 i2 o1 o2: nat}

(c1: circuit i1 o1)

(c2: circuit i2 o2): circuit (i1+i2) (o1+o2) :=

@circ a (i1+i2) (o1+o2)

(ns c1 + ns c2)

(fun bits inps =>

let (bs1, bs2) := splitat (ns c1) bits in

let (in1, in2) := splitat i1 inps in

(f c1) bs1 in1 ++ (f c2) bs2 in2).

Notation "l ^^^ r" := (vertical_compose l r) (at level 40, left associativity).

We will be working with exponential-size circuits a lot, so a useful definition is

twice which takes a circuit and vertically composes it with itself giving a circuit

with twice the inputs, twice the outputs and twice the number of switches.

Program Definition twice{a: Type}{i o: nat}(c: @circuit a i o): @circuit a (i*2) (o*2) :=

c ^^^ c.

Next Obligation. lia. Defined.

Next Obligation. lia. Defined.

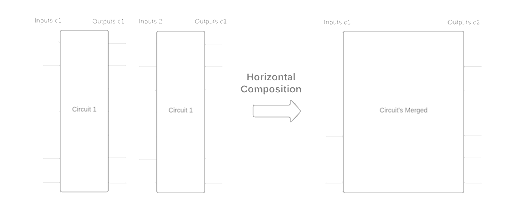

Horizontal

We now define horizontal circuit composition; we have two circuits, c_1 and c_2,

and we compose them to one circuit that first applies c_1 and then to its output applies c_2.

Fig3: Horizontal circuit composition

Contrary to vertical composition, we must provide a wire mapping of how the outputs of c_1 map to the inputs of c_2. This is

a finite map defined as WireLayer.

Definition WireLayer {a:Type} (n m:nat) := Vector.t a n -> Vector.t a m.

This definition is not ideal as it does not exclude, for example, a constant function that ignores the inputs. However, we allow such definitions in the general framework and specialize it when we get to permutation networks. This is our definition for horizontal composition.

Definition horizontal_compose {a:Type}{i1 i2 o1 o2: nat}

(c1: circuit i1 o1)

(c2: circuit i2 o2)

(wiring : WireLayer o1 i2) : circuit i1 o2 :=

@circ a i1 o2

(ns c1 + ns c2)

(fun bits inps =>

let (bs1, bs2) := splitat (ns c1) bits in

(f c2) bs2 (wiring ((f c1) bs1 inps))).

Notation "l >>> r 'using' w" := (horizontal_compose l r w) (at level 40, left associativity).

Permutation specification

For a circuit to be a permutation, first the number of inputs should equal the number of outputs. Second, every input should appear exactly once in the outputs. A first attempt to formalize permutations is to use the definition of permutation in the Coq standard library, which takes a bit of staring to understand. Here it is reworked for vectors instead of lists [eponier].

Section VPermutation.

Context {A:Type}.

Inductive VPermutation: forall n, Vector.t A n -> Vector.t A n -> Prop :=

| vperm_nil: VPermutation 0 [] []

| vperm_skip {n} x l l' : VPermutation n l l' -> VPermutation (S n) (x :: l) (x :: l')

| vperm_swap {n} x y l : VPermutation (S (S n)) (y :: x :: l) (x :: y :: l)

| vperm_trans {n} l l' l'' :

VPermutation n l l' -> VPermutation n l' l'' -> VPermutation n l l''.

End VPermutation.

The workhorse of the definition is vperm_trans which requires the proof author to non-deterministically provide witnesses of

intermediate rearrangements. However, this non-determinism comes at a cost to automation, as the proof author must provide the witnesses. Consider a weaker definition of permutations instead.

Start with the range function that generates a strictly decreasing vector of length n.

Fixpoint range(n:nat) : Vector.t nat n :=

match n with

| 0 => []

| S n => n::(range n)

end.

We can offset ranges by a constant and still get a strictly decreasing range.

Definition range_offset(off len: nat): Vector.t nat len :=

map (fun x => off + x) (range len).

Now we define a permutation predicate on finite functions, such that for all ranges, applying the function to the range returns a vector of elements and each one belongs in the original range.

Definition permutation_of_range {n: nat}(off len:nat)(f : Vector.t nat len -> Vector.t nat n): Prop :=

forall i, off <= i < off + len -> In i (f (range_offset off len)).

Definition is_permutation{i o: nat}(f: Vector.t nat i -> Vector.t nat o) :=

permutation_of_range 0 i f.

This weaker definition is easier to work with because it simplifies using the simpl tactic and does not

require providing intermediate rearrangements, allowing for proof automation. On the other hand, this definition of

permutation is weaker because it does not specify what happens, for example, when values are repeated, which never happens

when using range. It would be a good topic for future work to strengthen our proofs, so they use the stronger VPermutation predicate.

Notice we do not enforce i = o for the finite map here, but later when defining soundness and completeness, this allows for more liberal types.

Soundness & Completeness

A permutation network must be correct, both in terms of soundness and completeness.

Soundness meaning; for all the bits of configuration there is a valid permutation of range, meaning one is able to get all n! permutations. Completeness meaning; if there is a permutation, then one has all the bits of configuration (number of switches) present. Here are the definitions.

Definition sound {n m: nat} (c: circuit n m) :=

n = m /\

forall bs, is_permutation ((f c) bs).

(* a helper definition for completeness *)

Definition permutation_of_range_vector(off len: nat)(v: Vector.t nat len): Prop :=

forall i, off <= i < off + len -> In i v.

(* all permutations are possible. *)

Definition complete {n m:nat} (c: circuit n m) :=

n = m /\

forall (v:Vector.t nat m), permutation_of_range_vector 0 m v ->

exists bs, v = (f c) bs (range n).

Notice the helper predicate permutation_of_range_vector that works the same as permutation_of_range, but applies to vectors instead of finite maps.

Implementation (Benes network)

There are a few different permutation networks constructions to chose from. We chose a construction by Benes[3], which we found to be both intuitive, scalable and easy to define in a proof assistant.

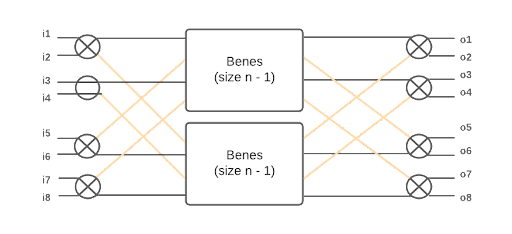

Fig4: Benes network recursive definition

The size of the Benes network is exponential to n which we pass as an argument to the construction of the circuit.

The number of inputs = outputs = 2^{S\ n} where S\ n denotes the successor of n.

The number of switches (bits of configuration) is equal to (2n + 1)2^n, this one

takes a bit of squinting and perhaps drawing a few Benes networks first.

Notice in fig.4, a Benes network is composed of two sub-circuits, two mutexes and two benes(n-1). A mutex is simply a vertical column of 2^n

switches and benes(n-1) is the recursive call to a Benes network with half the inputs and half the outputs. We stack two benes(n-1) and end up with three sub-circuits, which are then horizontally composed using a WireLayer we call cross-wires.

The cross-wires WireLayer

Each switch of the leftmost mutex has two outputs, and in order to allot for all possible permutations, there must be exactly one connection to the top benes(n-1) sub-network and one connection to the bottom benes(n-1) sub-network. What this equates to is each switch having a pathway to both of the networks. To achieve that pair-wise symmetrical mapping, we group adjacent inputs of size 2n in pairs of twos and get a

matrix A[2,n], then we transpose it to get A^T[n,2] and finally concatenate the matrix into a vector of outputs of size n*2. This transformation will place adjacent inputs a distance of n from each other in the outputs, meaning one input will be on the top benes(n-1) and

one in the bottom benes(n-1), as intended. Here is the Coq definition

Program Fixpoint group{a: Type}{n m: nat}(v: Vector.t a (m*n)): Vector.t (Vector.t a n) m :=

match m with

| 0 => []

| S _ => let (h, ts) := splitat n v in

h :: group ts

end.

(* concat *)

Program Fixpoint ungroup{a: Type}{n m: nat}(v: Vector.t (Vector.t a n) m): Vector.t a (m*n) :=

match v with

| [] => []

| h::ts => h ++ ungroup ts

end.

Program Definition cross_wires{a: Type}{n m: nat}: @WireLayer a (n*m) (m*n) :=

ungroup ∘ transpose ∘ group.

We omit the definition of transpose here for brevity. Also notice how the dependent types here are an excellent specification to the implementation provided which simplifies the proofs a lot.

Benes definition

Putting all of the above together we get the following Coq definition for benes.

Program Fixpoint mutex{a: Type}(n: nat): @circuit a (2*2^n) (2*2^n) :=

match n with

| 0 => switch

| S n' => twice (mutex n')

end.

Next Obligation. lia. Defined.

Next Obligation. lia. Defined.

Program Fixpoint benes{a: Type}(n: nat): circuit (2*2^n) (2*2^n) :=

match n with

| 0 => @switch a

| S n' =>

@mutex a n >>>

twice (benes n') using @cross_wires a 2 (2^n)

>>> @mutex a n using @cross_wires a (2^n) 2

end.

Our goal now, is to show benes is both sound and complete by induction on the argument n.

Proofs

It is no surprise that the proof follows the same shape as the construction of benes. Since there are two cross_wires on the left and right of our stacked benes(n-1), if we show they cancel out and by the recursive step benes(n-1) is sound & complete, so should benes(n).

Cross-wires involutive property lemma

So we start with proving the involutive property of WireLayer, we will show that cross_wires is involutive.

Lemma cross_wires_involutive: forall (a: Type) n m v,

@cross_wires a n m (cross_wires v) = v.

To do this, we first unfold cross_wires to its definition ungroup ∘ transpose ∘ group and we get the following helper lemmas to prove,

which we prove one-by-one, by induction on the length of vector v:

(i) group (ungroup v) = v;

(ii) ungroup (group v) = v;

(iii) transpose (transpose v) = v.

Number of switches lemmas

Since the number of switches of a circuit are opaque in the circuit record, we must present equations for ns for each circuit.

The culmination of those lemmas is

Lemma benes_ns: forall {a: Type} n, ns (@benes a n) = (2*n + 1)*2^^n.

To see why this is true, proceed by induction on n. The Benes network will always have an odd number of columns and each column will have

a length of 2^n switches.

Soundness & completeness of switches and benes

Finally, we can show proofs of soundness and completeness of each individual switch by the following lemmas

Lemma switch_sound: sound switch.

Lemma switch_complete: complete switch.

And then by combining all the above we can show soundness & completeness of Benes networks. Some additional lemmas are required along the way, such

as inclusion lemmas for mutex and cross_wires, meaning lemmas that show an element on the left of a circuit will be in the right of the circuit as well. Finally, those are the correctness lemmas for our definition of permutation networks.

Lemma benes_sound: forall n, sound (benes n).

Lemma benes_complete: forall n, complete (benes n).

Evaluation

We have around 600 total lines of Coq definitions. We also have around 400 total lines of proof, a 3:2 ratio of code to proofs. We attribute the small proof size to using dependent types and our use of Ltac proof automation.

Discussion & Future work

Our development defined and proved soundness & completeness of Benes networks in the Coq proof assistant. Using a circuit framework abstracts from the specifics of permutation networks, giving us tools to define more circuitry in the future. In addition, by using dependent types and reusable Ltac scripts, we reduced the proof overhead to a compelling ratio. In the future, we would like to suggest two promising directions.

-

A formalization of substitution networks, a two-way finite map used in the AES[5] family of algorithms. Together with permutation networks, they should give us the building blocks for specifying and proving AES in Coq.

-

A low-level implementation of AES that is a refinement of this model. The implementation could be through vellvm or kami, which would allow us to extract verified, executable LLVM code or BlueSpec definitions for AES.

References

-

How MIT’s Fiat Cryptography might make the web more secure, John P. Mello Jr

-

Beneš, Václav E., ed. Mathematical theory of connecting networks and telephone traffic. Academic press, 1965.

-

Waksman, Abraham. “A permutation network.” Journal of the ACM (JACM) 15.1 (1968): 159-163.

-

Daemen, Joan, and Vincent Rijmen. “AES proposal: Rijndael.” (1999).

-

Zhao, Jianzhou, et al. “Formalizing the LLVM intermediate representation for verified program transformations.” Proceedings of the 39th annual ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT symposium on Principles of programming languages. 2012.

-

Choi, Joonwon, et al. “Kami: a platform for high-level parametric hardware specification and its modular verification.” Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages 1.ICFP (2017): 1-30.

-

Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The comprehensive history of secret communication from ancient times to the internet. Simon and Schuster, 1996.